The excerpts below originate from discussions and articles related to the topic of multisig setups and signer incentives. They might not represent the implemented state but rather provide thoughts and vision on possible solutions to various challenges in multisig/governance setup design.

(by MinimalGravitas at Optimism Collective)

There is a general problem in DAOs of low participation in governance votes. Some DAO’s offer POAPs to Snapshot voters to encourage more voters, but while this increases the number of participants it does not necessarily increase the number of useful participants. What we want is a way to get people to apply more effort into their voting decisions, thus increasing the likelihood of a better outcome.

From reading discord chats there are certainly those who’s priority becomes obtaining the voting POAPs, with the expectation that this may be linked to further rewards in the future. This is likely to mean that they vote without maximizing the consideration of the proposal to be assessed, if your goal is the potential reward for having an ‘I vote’ sticker then who/what you vote for holds little importance. It is plausible that a significant fraction of the extra voters that POAP rewards elicit would fit this category, effectively farming the Snapshot votes rather than focusing time on deciding which option to select.

This problem seems conceptually similar to the attempts to gatekeep free tokens from Coinbase or Airdrops like Optimism behind short quizzes. The reward leads to users sharing answers or clicking multiple choice options quickly at random rather than taking the time to learn about the topic being presented.

My idea is to this is to mesh a kind of retroactive public goods funding into voting. If you’re not sure what Retroactive Public Goods Funding is then go listen to @karl on GreenPill: link

To integrate this into DAO voting, rather than reward everyone who participated in a vote, the effects of the decision would be evaluated retroactively and only voters who made beneficial choices would be rewarded:

This simple sounding tweak would encourage even those purely motivated by potential financial gain to try to pick the best outcome, rather than just any option, however there is an obvious issue of how to evaluate whether a proposal had positive outcomes or not. The effects may be obfuscated due to other overlapping proposals, or may be evaluated differently due to the subjective nature of the outcome’s ‘positiveness’.

As I see it the two options would be to either require proposal writers to set their own evaluation metric, or to have a group evaluating the objective outcome. The latter option could not be a simple vote by the same cohort as people would most likely claim to believe the outcome matched the way they voted (i.e. you’d say it went badly if you voted no originally, regardless of any outcomes) therefore a separate electorate (in Optimism’s case this could possibly be the Citizen’s House) is probably necessary.

In the former method, a proposer would have an interesting balance of incentives when setting their evaluation metric for a proposal. They want the proposal to seem as inviting as possible and so would want to maximize their claimed outcomes, but the people voting for them only get the reward if the claim is met and so may be more likely to vote for proposals with more modest claims. This could lead to the proposers underpromising, thus making voters more likely to expect the rewards of the evaluation criteria being met.

Clearly this concept needs more development, but I believe this should be an area we consider experimenting with in the iterative process of Optimism governance. While I’ve initially considered this from the perspective of someone voting directly, it would be equally applicable to selection of delegates. If you delegate your vote to someone who makes bad decisions you won’t end up being rewarded as much as if you had delegated to someone who makes choices with better outcomes.

(by Amplice at Gearbox Protocol)

- Multisig holders should be compensated in tokens, not in USD value of tokens. Just like every other role in the DAO, multisig holders should have access to upside. Governance can revisit the amount of tokens paid if we have a situation where the value of the token changes significantly in either direction

- Technical multisig participants have (in my opinion) a significantly harder job than financial multisig participants. They will be used to deploy new contracts, change params of the contracts, update allowedlists, and in emergency scenarios to pause operations. In other words, they need to be able to read code and understand what proposed TXs will do. Financial multisig just needs to be available and responsive to send tokens, which is significantly less difficult. For this reason, I believe that the technical multisig members should be compensated 1.5x to 2x more than financial multisig members.

(by C3: Crypto Compensation Consulting)

Because tokens are traded immediately, web3 organizations are subject to greater market criticism than traditional start-ups. Web3 organizations also have a decentralized and transparent governance structure where tokenholders have a strong influence on the organization’s overall operations. This decentralized governance structure creates a strong link between tokenholders and the employees.

Despite this relationship, very little progress has been made on aligning incentives of tokenholders and employees. Yes, both tokenholders and employees are motivated by an increase in token price. But, what happens during prolonged bear and bull markets? How do tokenholders ensure employees are working towards financial or strategic goals that continue to push the organization forward despite exogenous market factors?

Crypto’s governance structure is more similar to that of a publicly-traded corporation than that of a start-up. Therefore, we can leverage compensation mechanisms present at corporations, which better-align the incentives of the employee with that of the shareholder.

How can we ensure accountability of leaders via compensation and align incentives with token holders? C3 recommends the following approaches, which will be addressed in future articles:

- Utilize performance-based pay components, including performance tokens

- Implement token ownership guidelines to ensure leaders are holding tokens

- Promote transparent compensation reporting

(by C3: Crypto Compensation Consulting)

There are more tools that make performance pay more feasible (and attractive) for web3 organizations now than ever before, yet it is still rare in practice, likely because of historic precedent:

- Performance goals were difficult to define and measure. In the early days, web3 organizations were unsure about which performance metrics drove token return. Today, there is greater understanding, structure, and definition around key protocol measures that will drive performance. There are also plenty of third-party tools that measure such goals, thereby ensuring independence measurement.

- Performance goals were difficult to achieve. Volatile market conditions lead to uncertain performance achievement, which limits the overall effectiveness of performance pay. Volatility makes it difficult to set reasonable performance goals given error in estimation. Volatility is not going away, but it can be managed through thoughtful design (read more below).

- Undeveloped compensation governance processes have limited the ability to design, approve, and implement performance incentives. Compensation governance is constantly improving, and the prevalence of Compensation Committees and councils is increasing in web3. These entities provide the flexibility to work with outside experts to design performance incentives. After development, the committee can submit the plan for approval to the community. At the end of the cycle, the committee can provide an update on performance tracking and achievement, while also submitting the next plan for approval. This system of accountability ensures that there is sufficient rigor in the performance targets set by the protocol. A protocol should ensure it has an appropriate governance mechanism in-place that allows the community to regularly evaluate performance pay programs.

Looking ahead, we believe the use of performance pay will increase in web3 because it is an important mechanism to align the incentives of contributors with tokenholders, which fits within the ethos of decentralized compensation, and it achieves talent objectives that are otherwise unmet with time-based tokens. Additionally, unlike traditional corporations, web3 organizations can be creative on the design of performance tokens by mixing-and-matching traditional design types . This allows for greater customization.

The list below outlines major features web3 organizations and communities need to consider when designing performance incentives:

- Payment Type: will the incentives be paid in stablecoins or native tokens? Stablecoins will limit upside and thus the attractiveness, although it will protect the participant from downside risk.

- Performance Period: what is the time period that performance be measured over? A longer performance period will promote retention, although limit the accuracy in setting reasonable goals given market volatility.

- A performance period is not the same thing as a vesting period. An incentive can have a shorter performance period (e.g., 1 year), but a longer vesting period (e.g., 3 years) to ensure retention following performance achievement.

- To manage market volatility and performance achievement, a protocol can shorten the performance period such that goals are set on a more frequent basis. A shorter performance period limits error when setting goals and ensures performance cycles can be reset frequently.

- Leverage/Payout Range: how is leverage incorporated within the incentive? Does the participant receive less/more tokens for under/over-achievement of target goals? What is the range of payouts? Communities should ensure that they are not providing “free leverage”. Upside should be earned when stretch goals are met.

- Another way to mitigate volatility is to tweak the performance goal ranges. For example, protocols can set a flat payout around target. Or, set wide threshold and maximum goals to ensure a payout at either end.

- Metrics: Determining which metric will reward contributors is often the most important consideration because it affects what type of incentive will be used.

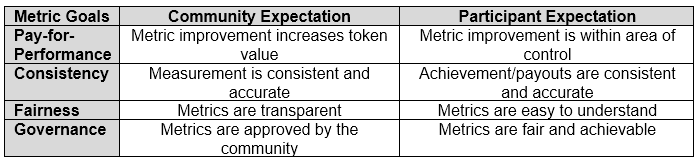

When selecting a performance metric, web3 organizations should make sure it meets the following expectations from the community and the participant:

Ideally an organization achieves all expectations via appropriate metric design:

- Metric Type: what metric will be used to determine payout? Will the metric be market-based (e.g., token price) or operating-based (e.g., Total Value Locked)?

- Metric Measurement: will the metric be measured on an absolute basis or on a relative basis?

- By measuring performance relative to similar peers, a protocol can strip away exogenous market factors and focus on value-added performance (more on that in later articles). Of course, this incorporate additional complexity.

- Goal-Setting: what are the appropriate goals that determine payout at target, below target, and above target?

Finally, it is important to note that performance pay is not for every type of employee. Generally, employees with greater risk profile should have a greater percentage of total pay in performance incentives. As you move down the risk profile, LTI should focus more on retention, and less on performance.

(by Tally)

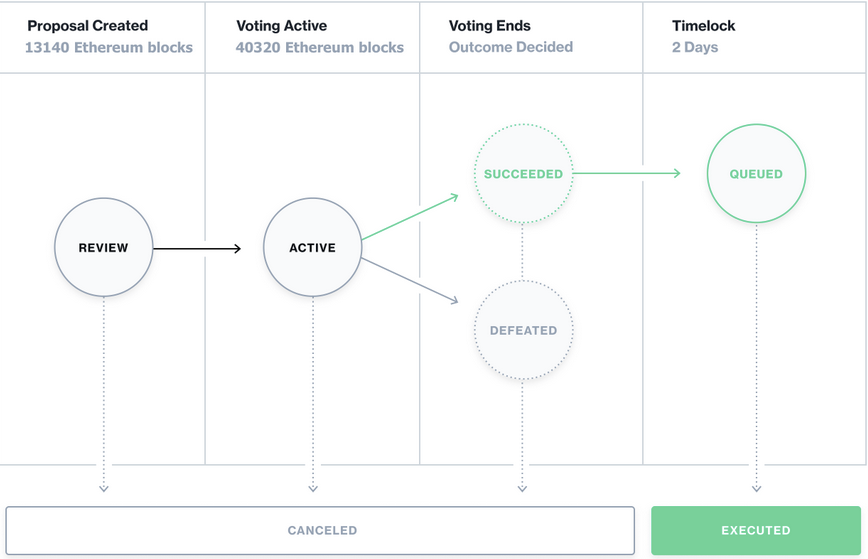

The OpenZeppelin Governor is a contract for onchain governance, designed to be compatible with existing systems based on Compound's GovernorAlpha and GovernorBravo. It is a modular system that allows different requirements to be accommodated by writing small modules using Solidity inheritance. The OpenZeppelin Governor system includes compatibility with existing systems, ERC20Votes & ERC20VotesComp, Governor & GovernorCompatibilityBravo, and GovernorTimelockControl & GovernorTimelockCompound. It also provides a guide on setting up a token, governor, timelock, proposal lifecycle, and timestamp-based governance

Governance process

Voting power is determined based on the number of tokens delegated to each address. This means users must submit a delegation transaction before their tokens will be included in governance votes. Users may either delegate to a third party, or self-delegate if they would like to participate in voting directly.

The basic unit of governance is a proposal, which represents a package of executable code to make specific adjustments to the underlying protocol. To prevent spamming, only users whose voting power exceeds the proposal submission threshold are able to submit proposals. Many protocols set this to 1% of total tokens, but each protocol can select their own preferred value. An optional proposal delay parameter allows protocols to delay the start of voting for a specified length of time after a proposal is submitted, giving time for users to update their vote delegation.

Voting takes place over a predefined voting period determined by the underlying protocol (e.g. Compound has a ~2.5 day voting period, while Uniswap uses a 7 day period). When the voting period ends, the system first checks if the number of yes votes exceed the protocol's quorum threshold (e.g. Compound currently requires 4% of total tokens to vote in support to meet quorum).

If the quorum threshold has been met and the vote gains majority support, the passed proposal is then placed into a timelock queue which delays code execution (this is currently set to 2 days for most governance systems). This timelock is intended as a security measure, allowing users to withdraw funds if they think the proposal is malicious or otherwise unacceptable. However, in contrast to Compound Governor which requires use of a linked timelock to function, OpenZeppelin Governor can be deployed and used without a timelock if desired.

If the proposer's voting power drops below the proposal submission threshold at any time from submission until the voting or time-lock period ends, the proposal can be cancelled. Finally, once the entire process has finished, the proposal can be executed and relevant code or parameter changes are implemented in the protocol. The image below shows the general process flow for proposals (note that the specific timelines shown for each phase correspond with Compound governance, but other protocols can choose different time periods).

Governor Alpha and Bravo

The original version of Compound Governor, Governor Alpha, was set up as an immutable contract. This means any changes to governance parameters (eg. quorum, voting period, etc) require deploying a new governance contract and transferring ownership of the governance timelock. This can create difficulty for integrated user interfaces or other services that need to point to a new governance contract address.

Governor Bravo is an upgraded version of the contract allowing for upgrades and changes to the governance parameters without migrating. Compound and a few other protocols have elected to use Bravo for greater convenience, and because any changes still need to pass a governance vote and timelock delay there are no additional security or governance risks compared with using the Alpha version.

(by 0xMikko at Gearbox)

All existing safe systems rely on time locks, leading to queued transactions being executed in a delayed manner. This process, while secure, introduces a two-fold limitation. Firstly, executing a single transaction requires gathering multisig twice – once for signing the queue and again for execution. Alternatively, adding two transactions simultaneously hinders the addition of an urgent queue transaction, reducing flexibility. This is a known issue among all governance implementations, be it via snapshot offchain or full onchain bravo.

As a result, any changes, even urgent ones, currently require a minimum waiting period of 3-4 days (2 days for the time lock and 1-2 days for signing in Gearbox DAO case). This delay significantly hampers the responsiveness of protocol management. For example, the Compound case above could have been solved if there were more roles in place that could avoid such situations.

While governance experimentation continues with regard to non-plutocracy models and centralization (quadratic voting and whatnot), today’s piece is about practical implementations of these events. The best governance is the one that doesn’t exist, but before we get there, we need functional governance which is able to secure the system and make it decentralized, but not be a bottleneck either.

Gearbox requires protocol management for various aspects like risk assessment, oracle updates, and the addition of new assets, all of which necessitate decision-making. In developing Version 3, our objective was to refine the governance process to make it:

- Convenient and cost-free: Retaining the voting mechanism on Snapshot ensures that community members can participate in governance without incurring any fees.

- Cross-chain capable: Preparing for deployment across different networks is crucial, as it expands the protocol’s reach and versatility.

- Rapid-response ready: Ensuring the ability to quickly adapt and implement changes is essential for staying relevant and effective in a fast-paced environment.

- Enhanced Security: Achieved through fostering transparency and providing a suite of open-source tools. These tools are designed to make every change in the protocol understandable, even for those without a technical background. This approach ensures that all community members can stay informed and contribute to a secure and stable ecosystem.

- Operationally efficient: Allowing for seamless operational tasks without overburdening the community with additional responsibilities.

I previously held the belief that onchain governance was the superior method, largely due to its numerous benefits. However, I’ve come to recognize its significant drawbacks:

- Voting costs: Each vote requires payment of gas fees, which restricts participation to those with substantial holdings, skewing representation. Hard centralization. Of course, security doesn’t come without costs, but this is not necessarily full-proof either.

- Cross-chain governance complexity: This process heavily depends on bridges and messaging used, introducing additional risks and complications. As such, in case your governance becomes cross-chain, you are only adding risks compared to the snapshot model. Your full onchain governance with gas costs doesn’t considerably look much safer in that case. As one chain, it does, but with 1+ chains and gauges - not anymore.

- Development and audit demands: Implementing a system where staked tokens can be used for voting requires considerable development resources and thorough auditing.

Suggested model combines the best of two approaches: voting is still happens on Snapshot as previously, however, token holders vote for concrete batch of transactions (like in Bravo), which would be automatically executed if voting was successful of desired chain. It's still costs zero for users, votes are protected by cryptographic signatures, and execution is automated. Additionally, this solution could be easily used across many chains.

In the upgraded Version 3 of Gearbox Protocol, a new ‘Governor’ contract has been developed to enhance the flexibility of protocol management by changing the interaction format. New model involves three key roles in the decision-making process:

- Queue Admin: This role is empowered to add transactions for execution. The new contract allows for multiple Queue Admins, enabling the integration of voting systems like oSnap and Snapshot X (to deliver voting results onchain), among others. This integration aims to automate the process of operational decision-making based on voting results.

- Veto Admin: This role functions as a rapid-response (3/10 or 3/12) multisig, capable of flagging a transaction. It’s designed to provide a swift reaction in cases where an added transaction is identified as erroneous or malicious.

- Executor: This role is responsible for executing transactions that have passed the time lock and have not been vetoed. In a significant shift from previous versions, any user can now assume this role, provided they cover the gas fees.

These roles collectively aim to streamline the governance process, making it more responsive and adaptable to the needs of the Gearbox Protocol community.

(by Dylan at IndexCoop)

When executing multisig transactions, it can be difficult to have confidence when confronted with a list of ethereum addresses.

You might ask yourself:

- Are these addresses correct?

- Where did these addresses come from?

- If using an execution doc, did I copy and paste the addresses exactly as they were written?

- Who had edit access to the execution doc?

- Could the execution doc have been edited by a malicious actor?

Gnosis allows users to import address books (in CSV file format) which label known addresses in the Gnosis interface. This can give you higher confidence that the addresses you are seeing are correct. If you see an un-labeled address, this can also serve as a gut-check confirming that the contract you are interacting with is new.

Without an address book, what exactly is happening in the gnosis UI can be difficult to decipher:

This is a screen shot of the same exact transactions from the same wallet (Treasury Multisig). It’s much easier to tell what is going on:

As a multisig signer you should be able to easily view transaction metadata, understand which contracts are being interacted with, what method is being called, who are the other signers thus far, etc…

An address book can be a dangerous dependency for the Coop. Users with edit access to such a list could update addresses and trick our multisig operators into sending funds to the wrong address.

By using Github we can enforce strict control over who can edit the address book and how those users can edit it. Any changes to the address book will also automatically be tracked in Git.

We invite all working group leaders, multisig signers & curious community members to begin leveling up their operational security by using the common address book above.

Link to IndexCoop's address book repository

(by szns.io)

The DAO governance space continues to evolve. Decisions around collectively owned assets all go through some sort of proposal system to create an action. The DAO proposal architecture manifests from a combination of soft proposals, hard proposals, and unilateral decisions.

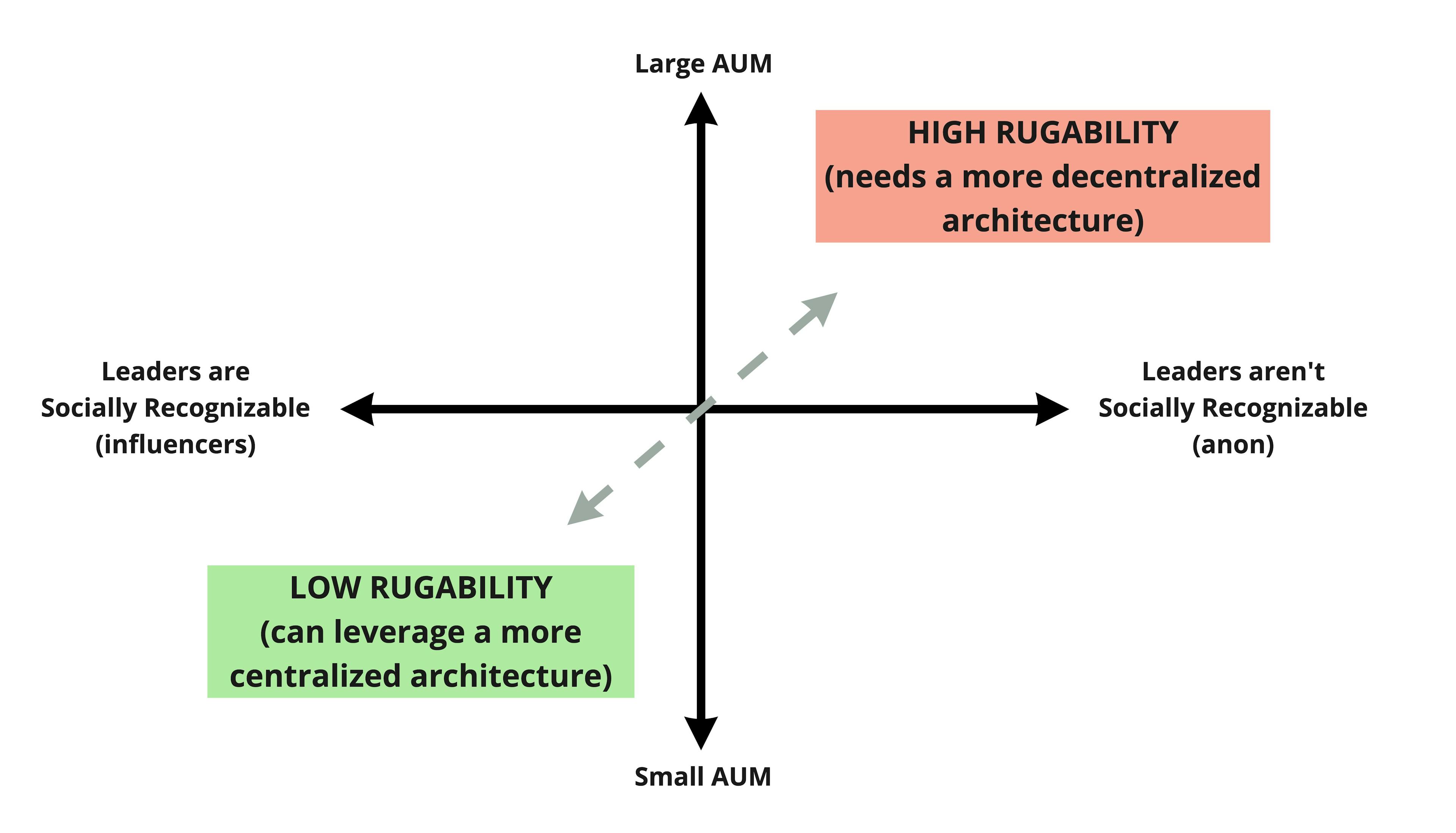

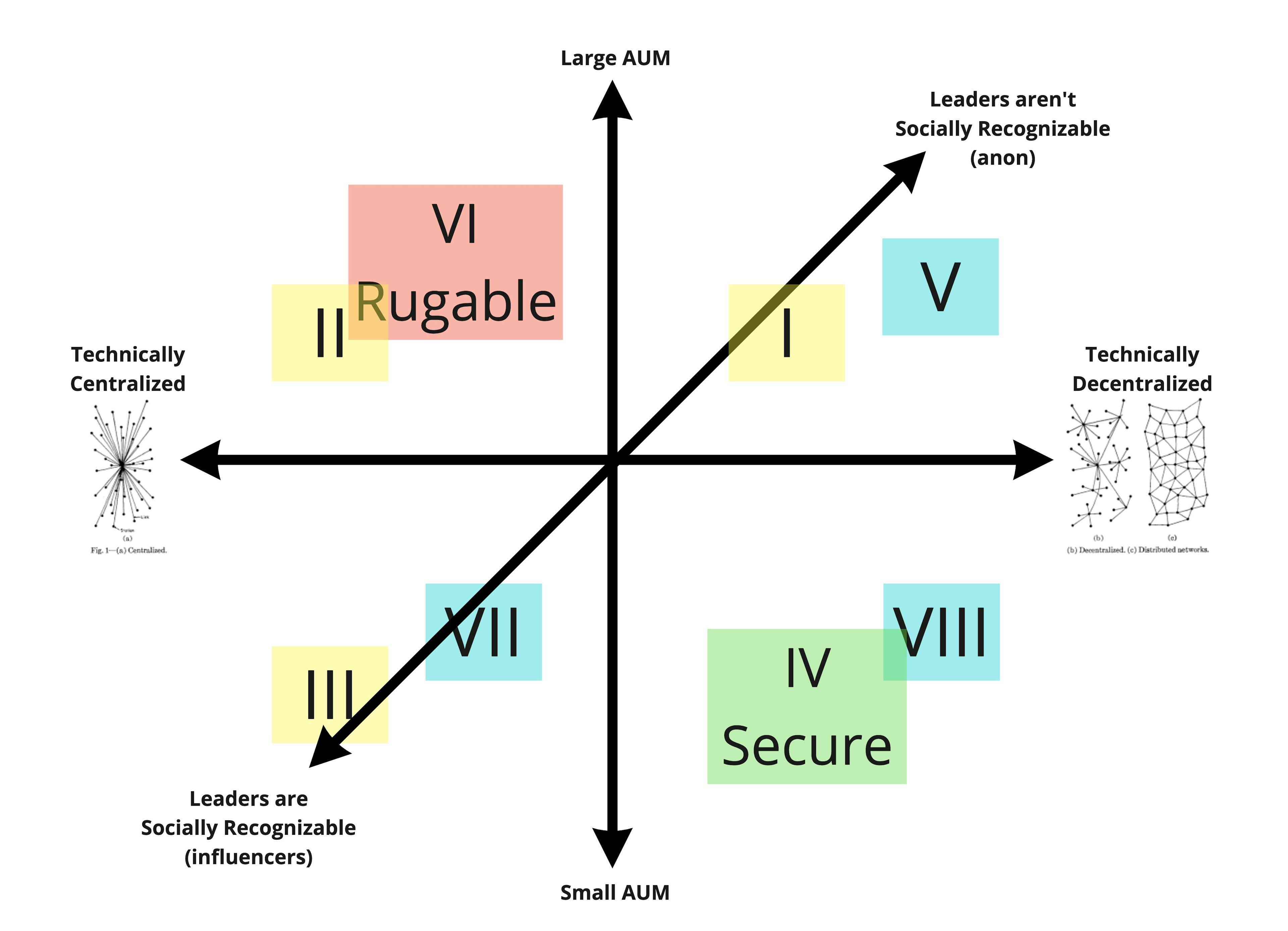

Strong DAOs build architectures accounting for the organization’s risk, defined by rugability. While less rugable DAOs may require nimble, centralized decision-making, more rugable DAOs require more decentralized practices to succeed into the future. Rugability

The extent to which DAOs exhibit secure practices varies greatly. New cases of manipulation and “Rug Pulls” occur throughout the ecosystem due to a lack of decentralized management of treasury assets as well as hyper-inflationary tokenomics that incentivizing dumping on the base of holders.

The simplest term for understanding whether a DAO or tokenomic system is safe to participate in should be determined by the degree of rugability.

$$ Rugability = f(AUM, Social Capital) = Value at Risk / Social Capital at Stake $$

Projects controlling large amounts of value hold higher degrees of potential damage to incur to the membership population. Additionally, if the leadership of the project holds no public social presence, there is nothing at stake to prevent them from “ruging” and running away with the money.

The way to combat rugability is through decentralization of the management systems controlling the collective assets. Systems with higher degrees of technical decentralization mitigate the degree to which they are rugable by the founding members.

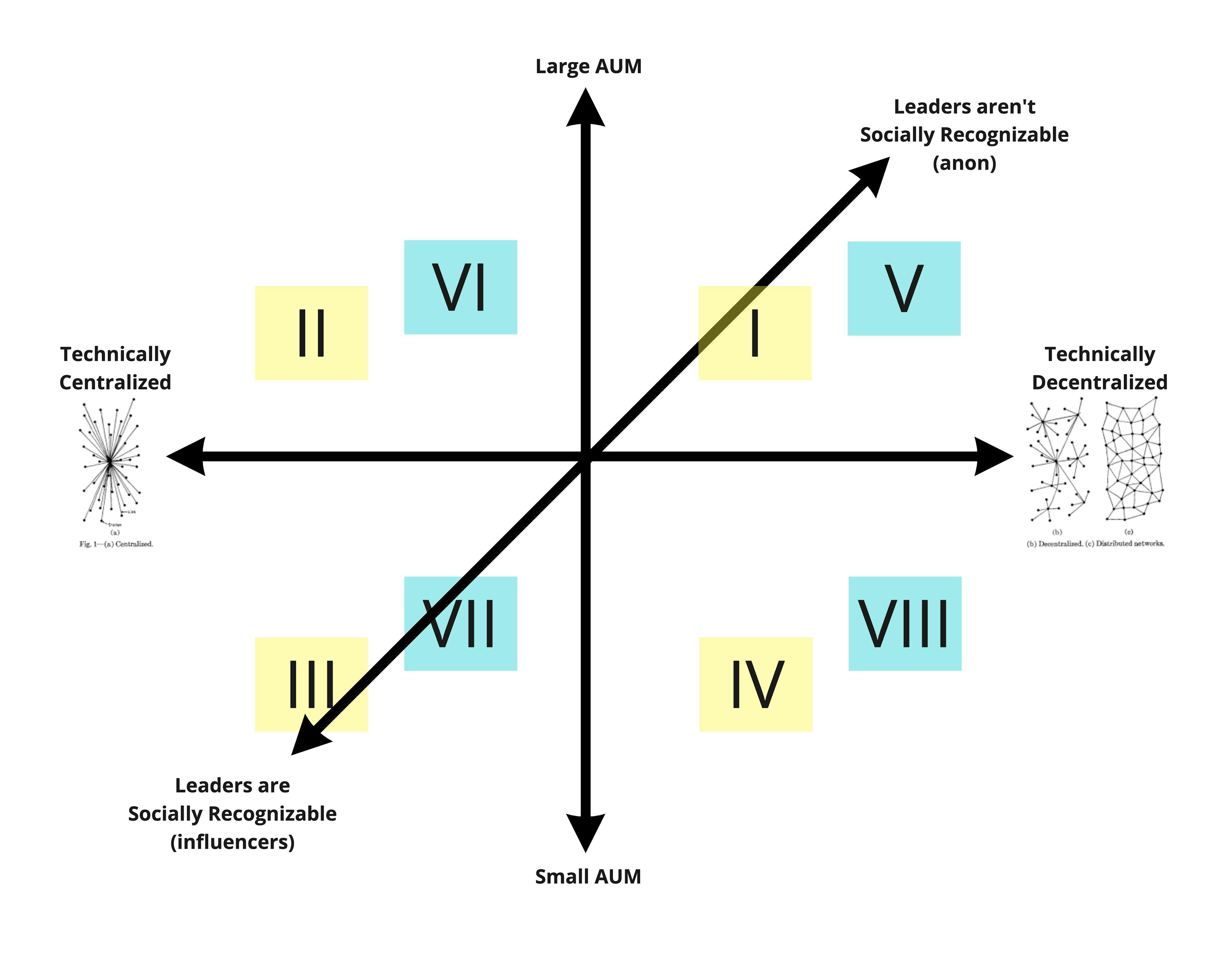

DAOs that fall into quadrant I (Anon Leaders with High AUM) require higher degrees of decentralization in their governance architecture. DAOs in quadrant III (Recognizable Leaders with Small AUM) can afford a more centralized and nimble governance structure.

How to determine the degree to which something is decentralized? It depends on the way the DAO structures decision-making power via Soft Proposals, Hard Proposals, and Unilateral Decisions.

Soft Proposals

This first category of proposals manifests various ways. Soft proposals gain a temperature check from the community via forum posts, Telegram polls, Discord emoji reactions, or snapshot proposals. This step in the process provides context for the community to understand a proposal, gives members an opportunity to voice their opinion, and gives the proposer feedback on the sentiment around their plans (ie. will this pass or fail before an on-chain vote).

Typically the soft proposal process should take the most amount of time, because this is the period of most thorough communication. The end state of the Soft Proposal should result in relative clarity or consensus around whether an idea will pass or fail a Hard Proposal. This process should always begin in communication channels (Forum, Discord, Telegram) and move into a Snapshot vote for communities that want extra clarity on where their token holders stand. Snapshot provides the most “legit” proxy of voting sentiment for on-chain action.

Depending on the community, and the complexity of the decision, soft proposals become more or less necessary. Decisions that clearly make sense and have fewer moving parts may require a very short (if any) soft proposal process. Further, communities made up of a tight knit group may only require a few messages in Telegram or Discord to find sufficient support for an idea. Forums are used for larger communities to develop a paper trail of logical context for themselves and new members.

Hard Proposals

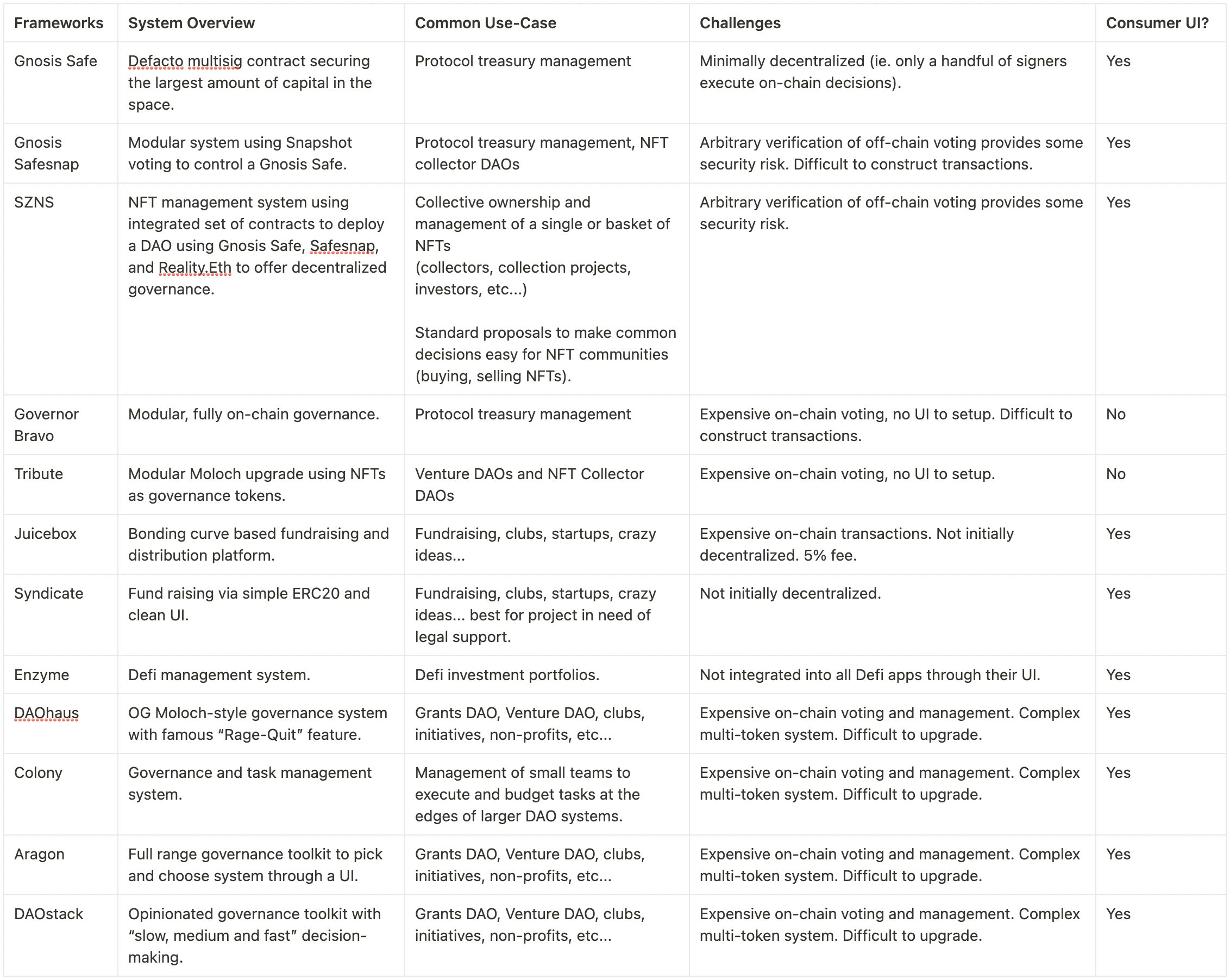

The hard proposal stage of decentralized governance actually commits an action on-chain. Unless the action in question is controlled by a multisignature wallet (ie. a wallet that uses multiple signers to manage assets) hard proposals typically result from a token vote. There are a variety of frameworks that use this type of tooling. The most modular, useful, and efficiently adopted being Gnosis Safesnap and Governor Bravo. Both of these frameworks have security and efficiency tradeoffs. Each of these contracts hold billions of dollars of value.

While I believe the two mentioned are most efficient for decentralization and upgradability, there are MANY DAO frameworks out there innovating on decentralized governance in a variety of interesting ways. See the full list here 👇.

There are obviously too many frameworks to experiment deeply with all of them. Any of the above systems can be used for any purpose, but each hold distinct tradeoffs with the way they function.

Unilateral Decision-Making

Despite the point of “decentralized” in DAOs, many require unilateral decisions to function. The extent to which a DAO should offer unilateral decisions to their leadership should correlate to the degree of rugability. Unilateral decisions should be given to guardians of DAOs in order to execute processes beneficial to the organization. If a DAO refused to offer any unilateral decision, all processes would take weeks to execute, limiting the ability for pragmatic and nimble development or coordination.

Many DAOs today still use a Gnosis multisig with 3 of 5 signers to enact any on-chain action. This is a great example of a unilateral decision-making process that is both highly nimble, but also highly rugable (only three people need to be convinced to sign a transaction that sends millions of dollars to their own account, not technically decentralized).

As a DAO offers unilateral decisions there should be proper understanding by the community of these risks involved. Often these unilateral systems are set at the start (ie. Gnosis multisig and Jukebox fundraise both start with a central leader with unilateral control). Alternatively, projects like SZNS offers a fully decentralized system that eventually may give Guardian powers for limited unilateral control over specific functions useful for the DAO community.

Conclusion: all together now

In order for a DAO to function there needs to be a combination of soft proposals, hard proposals, and unilateral decisions. The way each of these processes and privileges are implemented depends on the needs and goals of the community and organization, as well as the limitations of the technology chosen to foster these goals. In order to coordinate these processes properly, attention should be paid to the extent to which a DAO is rugable. Higher degrees of rugability require more time in the soft proposal process as well as more security in the hard proposals and unilateral decisions.

Below we take the graph above and qualify the Rugable vs Secure octants. Before choosing to participate in a DAO, this kind of graph may give a good proxy for the risk involved.

DAOs falling in octant VI (High AUM, Anon Leaders, Technically Centralized) account for the most rugable governance architectures whereas DAOs in octant IV (Low AUM, Recognizable Leaders, Technically Decentralized) account for the most secure and least rugable governance architectures.

(by Pamela Morgan at Empowered Law)

Separation of duties is a best practice within established corporations. Simply put, separation of duties is the division of certain responsibilities between different persons in the organization to add a layer of protection for shareholders and an accountability structure within management. For example, it’s common to require approval from both the CEO and the CFO for large expenditures, transfer or sale of capital and large assets.

The CEO maintains executive power, deciding what to spend; the CFO provides oversight and accountability for shareholders. This separation of duties provides protection against a broad range of scenarios both internal and external, intentional and accidental such as embezzlement from either executive, coercion of either executive, impersonation, and theft or loss of credentials. One party does not hold all of the spending authority and therefore cannot individually subject the company to significant loss by way of inappropriate spending.

Most traditional corporate bank accounts are set up to require multiple signatures to effectuate a transaction. Typically, a number of people are given signing authority on each account. These people are added to each account as “authorized signers”. For example, on an operations account, the authorized signers might include a bookkeeper, an accounting manager, the CFO, and the CEO. Cheques drawn from this account would require two signatures, such as the bookkeeper and the accounting manager, in order to be valid. If the bookkeeper leaves the company, the CFO or CEO could step in to sign cheques until a suitable replacement is found, without impacting company operations. The company would not need to worry about the bookkeeper independently withdrawing all funds from the account because transactions require two signatures.

Multi-signature addresses allow us to access the benefits of a traditional multi-signer account without bank reliance or constraints. Multi-signature addresses provide similar corporate governance measures, as transactions require more than one signature to be valid, however organizations should use caution when implementing them. In a traditional setting, banks play a hidden role in the transaction. While bank approval is not generally required for activity, the bank provides a method of recovery in the case of incapacity or death of an authorized signer. This is an important and relevant service for all accounts, including bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, and by excluding traditional banks from the process we must look to alternative solutions to this problem. Multi-signature accounts can provide an elegant, easy-to-implement solution.

If a signer approves the transaction but is unable to execute it, due to travel, illness, or a planned vacation (remember these transactions often require access to cold storage, secure internet connectivity, and PGP signed emails), the transaction can be executed by the third party. If a signer becomes incapacitated, through illness or death, the accounts are not effectively frozen because the third party can be asked to sign transactions.

Multi-signature addresses, by design, allow for an easy separation of duties. While traditional bitcoin addresses allow transfer of funds by presenting one “proof” consisting of a public key and private signature; multi-signature accounts require one proof for each required signature. Multi-signature accounts require M of N signatures, meaning you could set an account up to require 2 of 2 signatures, 2 of 3 signatures*, 2 of 4 signatures, 3 of 3, and so on. While the benefits of separation of duties could be achieved by implementing a 2 of 2, organizations should implement no less than 2 of 3 signatures, in order to provide for continuity in the event one of the signers or the signer’s credentials become unavailable.

Bitcoin’s Multi-Signature Addresses are Superior to Traditional Bank Accounts

Traditional banks can be compelled to hold, freeze, or confiscate customer funds because banks hold funds in custodial accounts and banks are profit-driven organizations subject to strict regulation. Because the bank holds the funds, the bank can be compelled to continue to hold them by an outside organization having influence over the bank, despite a request to release funds by the original depositor. Funds can also be frozen for administrative purposes, because of misunderstandings or clerical errors by the bank, because of bankruptcy or insolvency of the bank or for a myriad of other reasons, entirely unrelated to fault or behavior by the account holder. Simply put, your ability to repossess your funds is subject to bank approval.

Multi-signature bitcoin addresses are not subject to requests by third-parties, including governments, and therefore funds held in these accounts are not subject to holds, freezes, or confiscation. Control lies entirely with ownership and control over the signatory keys. If you can create the necessary signatures, nothing can stop you from processing a transaction. Conversely, without the necessary signatures, no one else holds power or control over the funds. They can neither spend them, nor stop the holders of the keys from spending them.